I. Introduction

In 2016, I stepped away from a 30-year accounting career to teach meditation to people suffering from depression, anxiety, stress and addiction. This blog post introduces the source, science and methodology behind meditation.

To reduce mental angst, it helps to understand human nature and how our mind works.

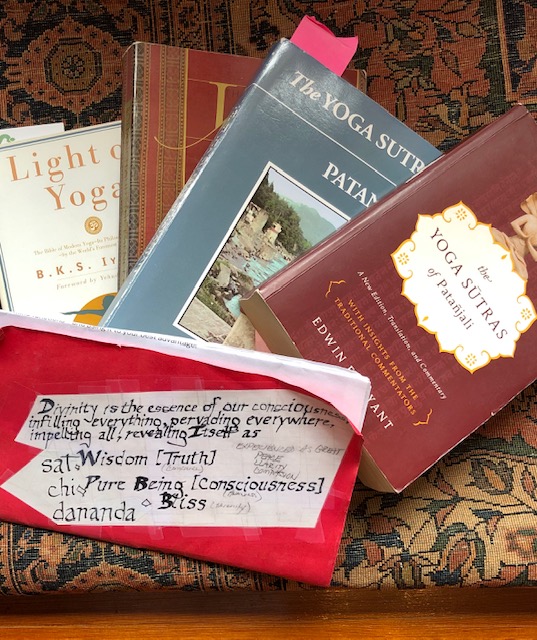

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras offers insights into:

- our physical, mental and spiritual constitution;

- the distinction between mind and consciousness;

- the difference between conscious and sub-conscious mind;

- the natural states of mind which color our thoughts;

- the types of thought we think;

- the cyclical codependency of our thoughts and behavior; and

- physical and mental exercises to promote lasting peace of mind.

II. Five things that affect our thoughts

There are five natural states of mind or “emotions” that color our thoughts; the first is the most impactful, and gives rise to the other four:

- Conflating our thoughts with our awareness OF them – the essence of who we are is not our tangible, functioning mind; rather, it’s our much more subtle, intangible awareness of what our mind is thinking or doing.

Thoughts are evidence of our mind; the awareness OF our thoughts is evidence of our consciousness.

Consciousness is the only thing known to man that science can’t explain. While what we’re aware of changes constantly, our awareness never does. Our awareness isn’t born, doesn’t function, age or die in a tangible sense the way everything else in life does. Our consciousness is constant, perpetual, timeless; it’s unaffected by the vagaries of time and space; it’s still, quiet, and benign. Meditation draws us closer to this deep unalterable aspect of ourselves.

- Ego – herein ego is the belief that we are only our body and mind (the parts we see in the mirror and hear in our head); specifically, not realizing that without the most miraculous part of us – our awareness of everything we think, say and do; which never gets hungry, bored, tired, sick, old, and isn’t affected by temptation or fear – we wouldn’t even realize we’re alive! Our consciousness is literally, utterly, always, and infallibly perfect.

- Desire and dread – these polar opposite states of mind are fueled by our bipolar (yin/yang or positive/negative) energetic constitution; to varying degrees, we’re either attracted to or repelled by literally everything tangible (people, places, things) around us.

- Fear – herein fear is stronger than dread, and specifically refers to our natural fear of dying.

Realizing the world of difference between our mind and consciousness, and the essentially divine nature of the latter, lessens the affects of the other four natural states of mind on our thoughts.

How do we overcome ego, desire, dread and fear? Patanjali suggests that we strive to constantly a) identify with the intangible, timeless, immutable aspect of ourselves (consciousness), and b) adhere to the Serenity Prayer, practicing Faith, Acceptance, Courage, and Wisdom.

III. Our thoughts affect our actions

Most of what causes our stress and anxiety are our own (in)actions; though ironically, most of our life experiences, starting with the time, place and circumstances of our birth, are consequences of actions beyond our control: those of other people and mother nature!

When learning to distinguish between thoughts and consciousness (we can affect the former; nothing affects the latter), keep the following in mind about your incessant thoughts:

- We effectively have two minds: our conscious ‘thinking’ mind, and our sub-conscious ‘doing’ mind; the former is home to the voice in our head while the latter silently runs-the-ship so-to-speak without our having to think about it (e.g., our sub-conscious ‘doing’ mind is responsible for breathing, walking, talking, internal organ and system functioning). Guess which one’s the troublemaker? Right.

- Here’s the key to controlling the troublemaker, our conscious, ‘thinking’ mind (evidenced by words or the voice in our head): it functions singularly like our heart and lungs: one beat, breath, and conscious thought at a time. It’s the aspect of our mind we use throughout the day to make decisions, analyze, and solve problems.

Skeptical that we can’t multi-think? Try simultaneously solving two math problems, or simultaneously counting and reciting the alphabet. Right. At best, we jump back and forth between tasks requiring conscious mental input.

- On the other hand, we’re typically unaware of our sub-conscious ‘doing’ mind; it runs in the background, and is perfectly capable of multi-tasking (this is the aspect of our mind responsible for walking and chewing gum at the same time). If we’re aware of it at all, this aspect of our mind is typically evidenced by actions, images and insights, rather than words.

- Every original thought is correct, incorrect, or imagined. Obviously, we can also recall previous thoughts as memories. The object is distinguish between these broad categories of thought in order to think correctly when its advantageous to do so.

The way to reduce depression, stress and anxiety, and relieve temptation is to think clearly and correctly, which requires that we practice a) distinguishing between our thoughts and our awareness of them, b) determining when we’re using our conscious versus sub-conscious mind (often simultaneously), c) recognizing whether our conscious mind is remembering, thinking correctly, incorrectly or imagining, and d) realizing to what extent our conscious thoughts are being influenced by ego, desire, dread and/or fear.

How do we calm our thoughts?

Practice. Practice. Practice. Calming our thoughts begins with learning to concentrate: focusing our attention. Once we can hold our attention still, we can begin to meditate: to refine our focus and hold our attention longer on whatever we chose to.

Personal opinion: the key to developing better thinking habits is to make it fun: begin by focusing on your senses individually (e.g., how many things can you hear or smell? How many physical sensations are you simultaneously aware of? Focus on the flavors of what you eat and drink – these are ways to “be present”, to hold your mind on the here and now – dampening fears of the future and regrets of the past).

IV. Our actions affect our thoughts

While our thoughts precipitate our actions, our behavior has profound, lasting affects on our state of mind.

How should we behave in order to positively influence our thoughts; specifically, to quiet our emotions, thereby calming and clarifying our thoughts? Patanjali prescribes a code of conduct and a regimen of self-care; the most impactful of which to sustained mental wellbeing is a list of ten “do’s and don’ts”:

Don’t (i.e., abstain from):

- Harm

- Deceit

- Theft

- Lust

- Greed

Do (i.e., observe):

- Cleanliness

- Serenity

- Courage

- Wisdom

- Faith

Additionally, Patanjali prescribes physical posture and breathing exercises to balance the muscular skeletal, and internal organ, systems of our body. It’s difficult to calm and settle one’s thoughts – to think clearly and correctly – with an agitated, aggravated, or energetically out of balance body. Patanjali’s physical exercises are the parts of the practice most commonly recognized as yoga.

V. Patanjali’s advice

Alternatively, Patanjali suggests that we can skip right to the chase and find the same degree of lasting peace of mind that eventually results from this physical/mental discipline – by turning our life over to God. Frankly, that happens naturally upon realization of the eternal nature of one’s own consciousness.

Patanjali’s most-cited, practical advice:

- Never give up – success herein depends on constant practice over an extended period of time

- Always let go – attachments, including regret and resentment, are impediments to reducing suffering and lasting peace of mind

In short, Patanjali offers a recipe to lessen distress by identifying – and providing remedies to address – the three aspects of the natural cycle of our behavior that result in consequences that either increase or decrease our level of distress:

Emotions > Thoughts > Actions > Consequences

Address the first three and the fourth will fall into place.

Blessings, Allan 🙏❤️🕉

Offering meditation lessons in Beverly and Marblehead, MA and online; call or text 617-599-8644 to schedule an appointment